Sprinkaan

Hierdie is die eerste deel van my Coenraad de Buys storie. Dit begin op die plaas Waterval toe ek maar net 10 jaar oud was...

I was flying low that morning—not from mischief, for once, but hunger. The sun stretched lazily over the Witzenberg peaks, and I hadn't yet decided whether to be a mantis, a locust, or just a fine mist over my beloved fynbos.

The year was 1771, and as far as I could tell, everything was going fine in the Cape of Good Hope.

Or as the locals would say one day: Die Kaap is Hollands—the Cape is still Dutch.

I weaved between pink watsonia and blushing bride, light as a morning breeze and just as unnoticed. Fynbos scents filled my antennae. I was contemplating a fat caterpillar for breakfast when a girl's scream shattered the morning quiet.

"Sprinkaan, come back! You can't leave me behind!"

Sharp and urgent—like a reedbuck's bleat of distress. Not anger or pain, but something rawer.

Betrayal, perhaps?

Sprinkaan? That could make a meal too.

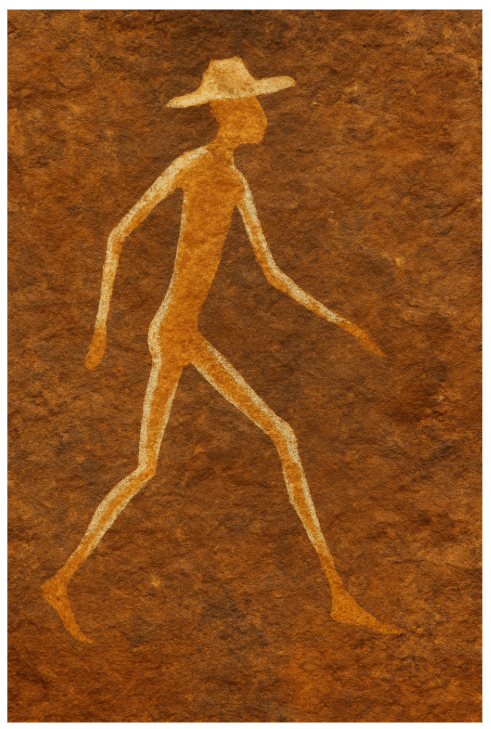

Curious, I rose above the flowering shrubs, my compound eyes scanning, my three eyes focusing. There he was, nearly on top of me—a slender boy with an oversized hat, just shy of ten summers.

He was walking with the fierce determination that only the very young or very desperate display.

He didn't look at me. No one ever does.

"I'm going," he said, voice low and swallowed by the fynbos. "You can come with me, or you can go back. I don't care."

The girl—his sister by blood and by the way her voice clung to him—stood barefoot on the sandy path. Her small fists were clenched white-knuckled at her sides, tears streaming down dust-stained cheeks.

"You can't!" Her voice cracked with desperation. "We don't know... we can't be sure Ma really did that."

Ah, I thought. Now this sounds like a story.

You must understand—I don't follow every child who runs from home. But something about this boy stirred the very air around us. The way he moved as if he'd already burned every bridge before crossing it. The way he didn't flinch, didn't look back, didn't beg forgiveness.

They called him Sprinkaan, I would learn. Locust-boy. A fellow insect. That amused me.

If you haven't figured it out yet, my name is !Kaggen. I can be everywhere and nowhere, depending on how I feel. The Bushmen call me a trickster god, though I prefer to think I help where I can—they just don't understand yet. I can see as far as I want into the past and pretty far into the future.

And I recognise this boy. I know where he comes from, and I have some idea of the man he could become. The trail-breaker they'll whisper about in borderlands. The outlaw. Maybe even a legend.

But I also know this moment—this precise heartbeat when his sprinkaan legs carry him, not just away from home, but into the wild shape of his own becoming.

Sansunna watched him climb toward the hostile slope where the Witzenberg lifted its shoulder in defiance. Her brother's bare feet found purchase on sand and grit, his fingers clinging to rough sandstone flanks as he dragged himself up through bush and grass. Six hundred seventy meters of struggle over three short kilometres—is what he needs to climb.

"If the leopards don't get you," she cried after him, her voice breaking, "those wild Bushmen will kill you for sure!"

That made him pause. Just briefly—the kind of pause where silence swells and hope flickers.

She stood panting in the path below, her voice raw with fear and fury. "They will, Coenraad! And no one will be able to save you!"

But he only turned his head slightly—enough for her to see he'd heard—and climbed higher. Jakob's voice echoing in the back of his mind: "Follow the Antjes River that flows like blood from that wound in the side of the mountain."

Sansunna stood alone as morning light caught the edge of her threadbare skirt, making it flutter like the tattered flag of a defeated army. She watched him disappear and reappear behind waboom bushes and massive boulders. Each time he vanished, her chest jerked with fresh pain, pushing out new floods of tears.With blurred vision and dark shadows filling the kloof, she could no longer see him.

She realised. He wasn't coming back.

She dropped to her knees in the sandy path, hands clasped tightly together.

"Heavenly Father... don't let the mountain eat him. Don't let him be swallowed by the earth like Cain. Please, Lord... let my brother come back to me... one day."

Even I stopped moving.

Not just the words but the urgency in her prayer—a powerful stillness—that I hadn't heard around a thousand campfires. It struck like an arrow through the heart of the earth. I felt it. Kou, the mountain felt it.

Sorrow, I think they call it. Yes. Even I feel it... sometimes.

From high above—where the Black Eagle soars and the air grows thin—she looked no bigger than an ant. A small girl in a hostile world where people, not animals, pose the greatest danger.

Sprinkaan scrambled up the ravine, his feet splashing water, as he crossed and recrossed the small stream.

The sandstone rose around him in strange shapes, carved by wind and water: blocks and puzzle pieces that giants might play with. He pressed his palm against one such formation and spoke to his friend:

"Klip, ek hoop ek doen die regte ding." Stone, I hope I'm doing the right thing.

Some ancient spirits, still sleeping in the rock, stirred and took notice. The climb became treacherous, every twist in the path presenting new riddles. On narrow ledges, he had to press his body flat against the rockface to maintain balance.

"Stay close to the kranz and don't look down," Jakob had warned.

Several times, cold fright poured over his heart, as he nearly lost his footing.

"Klip, hou my vas asseblief." Stone, hold me tight, please.

If you're confused, as I was, Sprinkaan has an imaginary friend named Klip—Stone. He speaks to rocks with unusual warmth, touching them lovingly with his palm. Strange, I know. But then, there are many strange things about this boy.

And still he climbed.

I watched from the hollow of a sun-warmed rock while my daughter-in-law, Kou (the Mountain) herself—began to warm toward him.

"You think he'll make it, don't you?" I asked her.

In the soft wind through waboom leaves, I heard her reply: "I would love for him to make it."

Sprinkaan heard something too, for he paused and spoke to his stone friend: "What are you saying, Klip? Do you think I'm going to make it?"

He was sensitive, this one. My curiosity grew by the hour.

Then Kou cleared the path before him, and the steep slope began to level as he reached the pre- summit of the Witzenberg.

The air was crystal clear. He turned for one last look at David Senekal's farm—patches of cultivated land in the valley below, rows of vines and fruit trees, a wisp of blue smoke curling from the farmhouse.

With a stretch of imagination, he could see old Jakob waving from the barn door.

I felt sad for this boy. He'd tried so hard to belong on that farm, worked with desperate intensity. Yet, David, a stocky short man, resented this much taller, handsome boy! His baby sister, Sansunna, slept in the house with the family, but there was no place for him. He slept in the barn with Jakob and the other labourers. The promised buitekamer, outside room, never materialised. He ate sitting on the kitchen floor, and after David read scripture and prayed, he was dismissed to sleep in the barn like property.

He'd experienced that same throat-tightening feeling when he and Sansunna rode on the back of the ox-wagon from Cogmanskloof to Drakenstein. He'd waited for someone to wave goodbye, but no one did. Before losing sight of the house, he'd waved anyway—perhaps someone would see.

Leaving Palmietfontein, his grandfather's wine estate, he searched the windows for a glimpse of his grandfather. Finding none, he'd waved anyway as they rolled through the impressive gates.

He'd been so excited about moving to his half-sister Gertruida and her husband David Senekal on the farm "Waterval" in the romantic-sounding "Land van Waferen." Little did young Coenraad de Buys know he was entering another cycle of hope, hard work, attempted belonging, and inevitable loss—a lesson he seemed doomed to repeat, over and over again.

But he had tried, truly tried, to make it work. To belong.

And here he was again. Exiled. Walking barefoot from the ruins of a broken home, carrying only a small rucksack, rolled blanket, water bottle, and his father's hunting knife—stolen and hidden a long time ago.

That familiar bitterness rose in his throat, but he removed his hat and waved at the farm below—at maybe no one. He wiped his brow, drank a sip from his water bottle, and turned toward a new future: The Bokkeveld, named for the abundance of game in the flatlands between mountains. He could not see it yet. He was on a gentle rise to the summit.

Jakob's voice, explaining in Bushmen detail, echoed in his mind: "Look for two big piles of rocks.

If you see a marsh in front of you, go to the right. Follow the rheebok's path. They like to walk between those rocks and over to the other side."

There it was, just as his Bushman friend explained it, less than 500 paces of a gentle rise and he was on the summit.

Surprised by the plateau of grass that stretch out in front of him, he looked across to the mountains on the other side. There was no notch that he could see! Did he go wrong somewhere? The next marker that he needs to look for is that notch in the mountain.

The boy could feel some uncertainty rising from the pit of his stomach. The old Bushman was was clear about it. Did he maybe make a mistake or misunderstood his instructions?

He took a deep breath and just scanned the hills on the other side of the valley. He could see two valleys that met and when he looked carefully, he realised there were two mountain ranges behind each other.

Yes! There it was, the notch in the first mountain across the flatland. Jakob's voice came back strong: "Aim slightly right of it, and when you reach it, follow the easy road trending left, toward the sun." There it was—a jagged cut in the distant Bokkeveld ridge. A passage into another world.

He descended carefully. The slope was gentler—only three hundred meters over two kilometres—but his legs had grown tired. Sandstone crumbled underfoot, around him big sandstone blocks weathered into strange shapes: sleeping faces, forgotten beasts, gates to vanished realms.

Excitement built as he stepped into this new, grass covered world, turned golden by the summer sun. The Bokkeveld spread out before him, wide and quiet, filled with promises not yet revealed. Soon he reached the valley floor, following white sandy trails left by countless animals.

He walked barefoot across five kilometres of rough, broken veld, his shadow stretching eastward toward his destination: the base of the next mountain. "Follow your shadow," old Jakob had once said, and it felt as if the Bushman walked beside him.

The late afternoon sun stretched Sprinkaan’s shadow long and thin across the sandy path. Ahead, a stand of wabome—tall, ash-grey proteas with cracked, weathered bark—whispered gently in the breeze. Finches chirped nervously from somewhere within the clump. Sprinkaan had heard birds do that when an owl was sleeping nearby.

Beyond them, the sandstone walls of the Cederberg glowed gold in the afternoon light, their peaks burning quietly against the deepening sky.

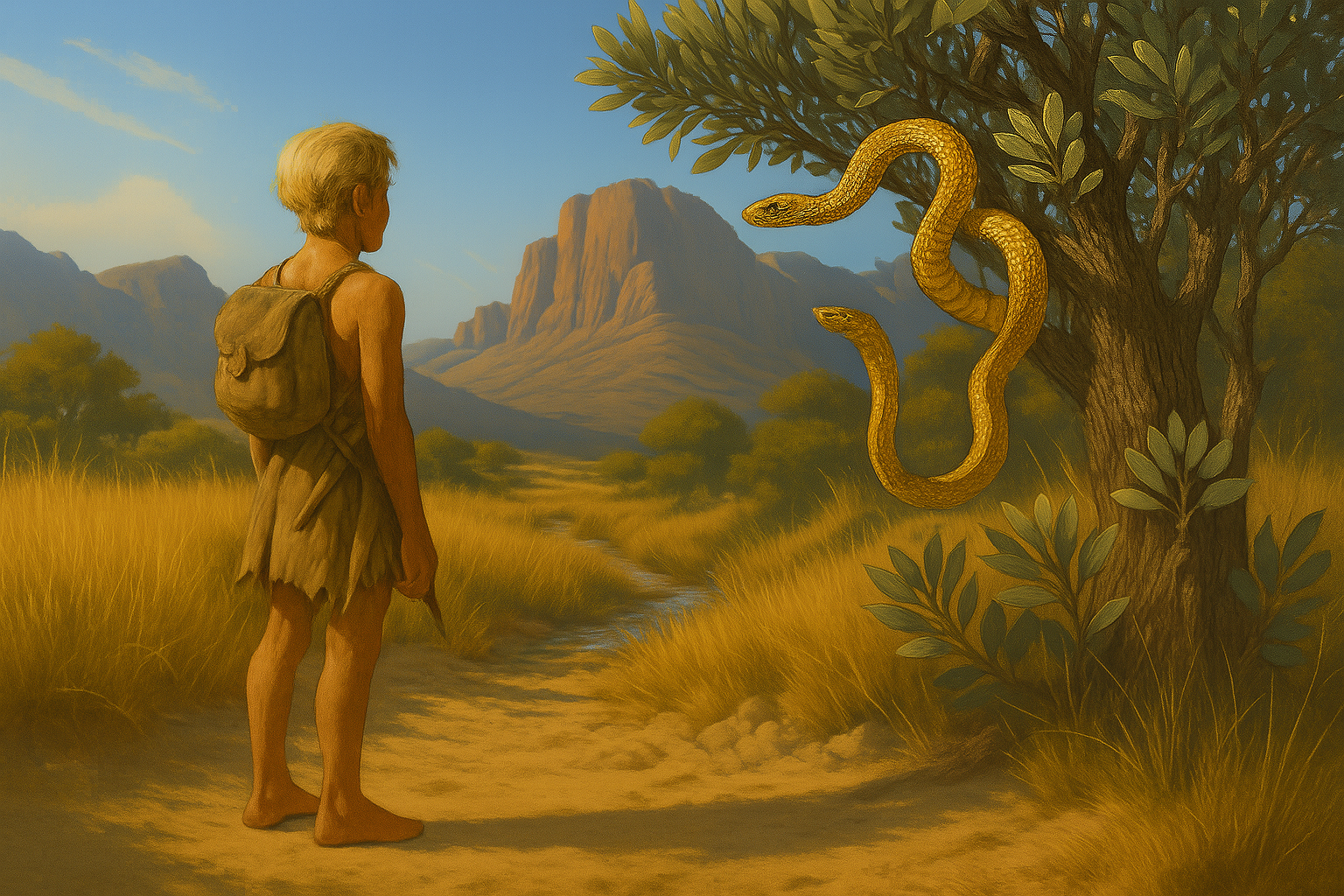

Then a branch moved oddly!

He froze.

Two geelslange—Cape cobras—were entwined on the branch, locked in a slow-motion duel. Their scales flared like brass in the sun, wrapped around each other and the branch, like a twisted rope of koeksister. Bodies as thick as his arm writhed and flexed in deliberate combat. It was a mating duel—silent, ritualistic. Which one would win?

Sprinkaan stepped closer. The snakes, so intent on their struggle, paid him no notice.

Suddenly, one lost its grip.

It dropped.

Sprinkaan flinched as the snake hit the ground with a thud, twisted once in the dust, then shot off into the undergrowth, leaving a single winding track across the sand.

The victor remained a moment longer, tongue flicking, head lifted in victory, then glided along the branch and vanished into the grey foliage to claim his prize.

Sprinkaan stood still. His heart was quiet. He had come in search of freedom, but the veld had shown him something older—older than stories, older than memory, part of survival.

Approaching the mountain, he noticed that his shadow was growing longer and longer. The sun dipped behind the ridges and a welcome coolness spread over the valley.

He stepped forward again, this time softer.

The path curved around a marsh shaped like a horseshoe, and crossed a narrow stream—too overgrown and shallow to drink from. He pressed on, looking for better water.

Slightly to his right, at the foot of the mountain, a dense green bush caught his eye. There might be water there.

There was a copse of trees standing among a heap of weathered boulders—great sandstone blocks, strangely out of place on the flat valley floor.

He looked up at the notch in the mountain and wondered, Why these rocks? Why here, right in front of that gap?

He reached a stream and knelt beside it—a friendly trickle of water that seemed to speak. Perhaps it did.

He plunged his hands into the current, holding them there for a long time. The cold, living water wrapped around his fingers. Beneath its surface, even his hands looked like strangers. He splashed his face, rubbed the back of his neck, and drank deeply with cupped palms.

Revived, he followed the animal path toward the rocks and the trees. He wondered what the creatures sought here.

He approached one of the larger sandstone blocks and gently placed his hand on its surface, it felt nice and warm – maybe it was alive?

"Klip, hoe het die rotse hier gekom?" Stone, how did these rocks get here?

He stood in silence, waiting for a feeling—some trace of an answer.

Then, with a soft plop, a half-eaten fig dropped into the bed of leaves at his feet. He looked up.

A flock of pigeons were feasting on the ripe fruit of the wildevy trees above him. The trees were full of figs, heavy and dark.

He smiled.

Dinner was sorted.

Sprinkaan moved some dead branches and stones away from his big rock.

"Klip!-waar is jy? Ek wil daar by jou kom slaap." Stone! – where are you? I want to sleep there by you.

Maybe he felt safer closer to his imaginary friend. There was no time to gather wood and he was too tired anyway. What he would learn in time is that stone absorb heat during the day and if you picked the right friend to sleep next to, you will sleep warm all night.

In the distance two jackals were telling everyone on the plateau, that they were so very hungry… But then everyone knows, never to trust a jackal, they are far to clever – just ask the wolf. Back then any kind of hyena was called a wolf. He hardly started to review the events of the day, when he fell asleep on a bed or wild fig leaves, next to his friend, Klip.

That night, beneath the bitter stars, the boy lay curled under his blanket, with his back close to the huge block of sandstone. In the dark, unseen by the boy, I was perched upon a branch nearby. My antennae twitching and testing the air, while I watched the sleeping child. Men are what they dream and I want to be nearby to learn more about this Sprinkaan and what makes him what he is. "And the approaching dream is not his choosing. It is the mountain’s gift. Or its test, I thought to myself.

Let me share the dream with you just as I can see it play out in his mind.

Young Sprinkaan sat quietly just outside the little stone house on the farm Ezeljacht, nestled in a curve of the Kochmanskloof, near what would one day be called Montagu. The late afternoon sun warmed his face and shoulders, and he let himself enjoy the simple stillness of the world around him. Sparrows chirped and fluttered in the corner where they were busy building a nest under the thatch, and turtle doves called softly from the branches of a wild olive just beyond the barn where his father was working.

He let his mind drift. He wasn’t thinking of anything in particular — just fragments of warmth, the touch of the sun on his skin, the smells of food and fire in the kitchen behind him.

Then, suddenly, a sharp cry broke through it all — a shout from the barn. He jumped to his feet.

From the barn, his father came tearing up the path toward the house. But behind him — less than a hundred paces away — was a huge male lion, running in a dead straight line, focused entirely on his father as if it meant to strike him down.

Coenraad froze for just one heartbeat. As if in slow-motion, he could see the lion’s mane shaking and blowing in the wind as it charged towards his father. Then came his father’s voice, loud and desperate:

"Kry die roer!” Get the gun.

With his heart pounding, he grabbed the gun from inside the house and rush outside. He held the gun out towards his dad but his father did not even see him and ran straight into the house. The boy turned around to shoot the lion – nothing, no lion in sight. He ran back into the house and slammed the door behind them. His eyes took a few seconds to adjust to the light and that is when he saw it!

His father was lying on his back and standing over him, leaning forward, was – the lion! Impossible, he thought, because the door was closed. While his eyes adapted to the darker room, he was horrified to see a big brown creature bearing down on his father. Someone — or something — cloaked in a thick brown robe, the colour of the lions mane, was there – with a deep hood pulled low over it’s face. The figure was silent. Still. Watching. His father looked terrified and helpless. And whatever light came through the small window, seemed to vanish inside that hood.

Coenraad squinted. Was it... his mother?

"Ma?" he called out.

At that, the figure slowly turned to look at him — and what he saw made his blood run cold.

There was no face beneath the hood. Only a black surface, like a mirror polished with ash, and the more he looked, the more it seemed to shimmer — as if behind that blankness was something vast and cold and ancient. Something that looked back. Slightly fogged, reflecting only his own frightened eyes. The boy stepped back. The creature raised a woman’s hand, as if to hush him away, and the mirror shattered into hundreds of razor sharp daggers — that plunged like a storm of broken glass into his father’s stomach.

The daggers pierced his fathers abdomen. His father cried out — a deep, wounded roar — and curled into himself, hands clutched to his belly, legs drawn up tight in terrible pain.

Now the scene changed. He was running across the veld, bare feet over sharp thorns, chased by a cloud of black ravens, with daggers for beaks. He ran towards the rocks and shouted for Klip to open a door.

He stumbled and fell.

The earth beneath him opened like a mouth and swallowed him whole.

He woke up in shock!

In the distance we can hear a nightjar and on the other side of the valley, a round bellied moon, hovering just above the tall mountain ridge, pale and ghostly against the deep blue that still clung to the western sky.

I was still sitting on the same rock, also out of breath, blinking all my eyes and lowering my antennae. Thinking to myself:

"There is no wound so deep as the wound of being unwanted." I thought that, with no pity, only truth. The boy needs to deal with the loss of both parents, especially his mother, and the self he does not yet understand."

With the moon sliding behind the mountains, the stars came out brighter but that was no consolation for young Sprinkaan. His face was tight and his legs were twitching beneath the blanket. He sat up with his back against the rock and pulled the blanket up to under his chin.

While we watched the dark slowly fade into dawn, I was thinking to myself, he really only had two choices with the cards that he was dealt with: He could allow the world to emasculate him or rebel against the events and blaze his own trail.

Overhead, the last few stars faded into a softening horizon, while the east burned slowly into crimson. Thin streaks of cloud stretched out across the sky like brushstrokes, catching fire with the first hints of morning: pink, then amber, then gold. Far off, the nightjar gave its final cry.

Coenraad pulled the blanket closer around his shoulders and just sat there for a long time — breathing, watching. Grateful. Not only for the beauty of it, but for the strange and quiet fact that he was still alive.

Above, the peaks of the Witzenberg a round bellied moon was getting ready for bed. Around her the tips of the mountains caught the first splashes of sun, glowing with a light so pure and untouched it seemed otherworldly. The air was cool and friendly. The picture in front of him looked like a painting.

“Dankie Here vir nog ‘n dag.” Thank you Lord for another day. The boy said his morning prayer as he did most mornings. He didn’t know it, not really — but somewhere deep inside of him, he felt it: something is trying to tell him that he was right about his parents. He did feel a bit guilty because he was starting to forget about them. Yet they still seem to have some kind of hold over him. This boy have good instincts, I thought to myself.

Somewhere up on the cliffs, a dassie let out a sharp, birdlike squeak — the kind they make when an eagle or a leopard passed nearby.

The sound pulled a memory loose. Jakob’s voice, low and mischievous, came back to him — the story of the Leopard and the Dassie. He had a number of stories about the leopard and the dassie. Sprinkaan smiled faintly in the morning light. Some silly stories, he thought.

He stretched in silence. He rubbed the sleep from his eyes and slowly sat up, feeling the stiffness in his shoulders and lower back. He thought about his old friend Klip — silent, weathered, eternal. Reaching behind him, he laid his palm on the cool sandstone, acknowledging his friend.

With the image of his father, curled up on the kitchen floor, still clear in his mind, he exhaled. Steadying himself, physically and mentally, he began packing his meagre belongings.

He took a moment to scan the surrounding terrain. The kloof was still cloaked in shadow, but the day was warming nicely. Jakob’s instructions drifted back to him — not just the words, but the rhythm of them, the way Jakob had spoken of these paths and valleys as if they were old friends. “Cross at the notch in the mountain. Take the easy road. Once you're in the next valley, turn left. Follow the sun up the valley.”

And with that, he stepped into the new day — eyes open, ears listening, walking in a world where every rock looked like it could speak and every track could tell you a story.

He shouldered his pack and set off at a steady pace, his body still stiff but warming quickly as he began the day’s climb. The path wasn’t nearly as harsh as the day before — more a steady ascent than a scramble — but it still rose sharply, winding along the side of the kloof toward the crest of the next ridge. He followed the sun, angling along the kloof towards the ridgeline that Jakob had spoken of with quiet certainty.

The first stretch lifted him nearly three hundred metres up from the valley floor. He paused often, drinking sparingly, resting beneath stunted trees and flat overhangs. The sun climbed with him, and so did the heat, but the path remained forgiving — as if Jakob had chosen it not just for its direction, but for its mercy.

When he finally reached the notch, he found himself between two barren sandstone koppies, with lots of sandstone blocks strewn all over the place. In the valley the waboom grew so thick now that he had to climb out to the one side. He climbed onto a big block of sandstone...

And then he saw it.

The narrower valley to the left and beyond, holding the promise of freedom. To his right the lowland with monstrous mountain peaks far in the distance. It was much greener down there and he could see farms and small buildings, exactly as Jakob described it.

“You can find other Dutch people there and maybe they will give you a job. It would be much safer than to go deeper into the Cederberg.” Sprinkaan shook off that idea – he was definitely not ready to go and work on another Dutch farm. He turned his attention to the narrower valley to his left. The one that would lead to freedom.

The shape of the valley was laid out like a left hand, a piece of fore-arm, then four fingers heading north and a thumb-sized valley off towards the east. It looked golden with the sun on the grass. The floor stretched far and level, bordered on each side by a long ridge of mountains. Dappled with lots of waboom shadows and folded ridges in the distance. On the left-hand side, as Jakob had promised, a faint trail curved along the valley floor, heading towards the four fingers.

He grinned — not as wide as the previous valley, but full of promise. With a cool breeze in his face he just stood there — letting it wash over him, pulling sweat and memory from his skin.

He began the descent, slowly, carefully — dropping a hundred metres down the gentler slope, minding his knees and footing. With each step, the land seemed to open a little more, welcoming him, unfolding.

By the time his feet touched the level ground of the valley floor, the nightmare of the night before felt further away — like something folded back into shadow.

Sprinkaan thinks of Jakob and how he is now thinking about deviating from his clear instructions.

“Kleinbaas”, Small boss, he said, “if you don’t go to the Dutch farms, just continue north along the valley.” Holding out the back of his left hand he showed me with a finger, down the forearm and right towards the thumb. There he said the mountains open up and you can find the plains where !Kaggen fought with the baboons and what the Dutch hunters call “Baviaanshoek” Baboon Corner. You will be much safer there because there is no Bushmen clan that live nearby. Just follow the water, that will take you to the east. You will be in the Bokkeveld, a beautiful part of the world.” And Sprinkaan walked on, following the road signs just like Jakob explained it to him.

The walk was easy. The yellow sand underfoot was warm but loose, and his feet made hardly a sound as he walked. Clusters of bush and tough grass clung to the ground, with the occasional splash of green where the water seeped closer to the surface.

As he continued, he saw game more frequently. A small group of rooi ribbokke red mountain reedbuck, darted across his path, their shiny coats flashing red-brown between the brush. Not far beyond them, a pair of klipspringers perched high on a boulder, still as statues, watched him with bright eyes. With their ballerina-like hooves gripping the bare rock as if the cliffs themselves are holding them up.

The northerly breeze, kept him cool, making the walk pleasant and peaceful. The land felt generous. Springlands let himself enjoy it.

This was the heart of the Koue Bokkeveld, Jakob had said — cold in winter, wild in summer, but always rich with life if you knew where to look. And today, it was living up to its name.

Ahead, the stream curved again, fed by fresher run-off from higher up. The sandstone formations grew taller, more dramatic — broad pillars and walls, golden and wind-scoured. He turned a bit left and followed the bigger stream leading towards a kloof in one of the highest parts of the mountain. He needed to criss-cross the steam a few times because of sandstone blocks and matjiesriet, carpet reed, but he adjusted his pack and walked on, smiling. This was a beautiful place, he thought to himself, just like Jakob showed it to him in his stories.

There is Jakob on his mind again! That old Bushman must have been almost like a father to him. I remember Jakob and if I didn’t stop the eland that day he would have died here in the Bokkeveld. The Bushmen were too arrogant for my liking that day. They already killed a ribbok, “mountain reedbuck”, before noon, when on their way back they surprised a small herd of eland drinking at the fountain. The Bushmen walked a wide circle around them to create the impression that they are no threat to the eland. While slowly walking through the fynbos they concocted a plan that didn’t suit me at all.

Jakob and two of the younger men will fall behind and once behind the clump of proteas, would duck down and hide from the eland. Their mission was simple, wait for the majority of the hunters to proceed up the valley and take the reedbuck back to camp. The eland that can’t count will see that the hunters are leaving the area and once they feel safe, they will return to the fountain to drink.

Jakob and his team will position themselves in such a way to give the eland herd a big scare, start chasing them in an attempt to isolate one of the old cows and then coaxed her up the valley towards the camp.

Let me explain what they are trying to do here. The eland are the biggest antelope in Africa and when you kill one all that meat needs to be carried to the camp before the scavengers descend on it. What Jakob and them are trying to do is heard the eland towards the camp and at a suitable place close enough to the camp, the eland would be ambushed and killed.

Eland being such majestic animals do not like to be chased down by the nimble Bushmen. The eland won’t run downwind either because they don’t know what could be waiting there for them. They hate it when the Bushmen use their painted dog strategy and take turns to chase them. Eland tire quickly when being chased down like that and sometimes the older ones will just stop. Push their rears into a bush or against some rocks and fight their attackers.

Jakob and his team managed to isolate the oldest of the cows and slowly guided her upwind and into the valley leading to the Bushmen camp. Coriga was one of my favourite cows and she had the softest most beautiful brown eyes. She was getting on in her eland life and normally, it would have been a good thing for her to feed someone with the meat from her body when she moves to the spirit world. Just on this day, I was not happy with those greedy Bushmen and wanted to teach them a lesson.

The wind started to blow much stronger now to cool Coriga down and to carry the scent of her fear to the strong young bull that protected this small herd. He came from behind and surprised Jakob that was completely focused on chasing the cow op the valley. Jakob didn’t see it coming and was flung high up into the air. One of the horns pierced his upper leg and the might of that huge neck on the young bull, picked him up with such force that it broke the bones in his upper leg.

The cow saw the opportunity to escape and the bull charged towards the other two hunters that ran away as fast as the wind. The rest of the hunters watched in horror from their ambush site. The bull turned his attention back to Jakob that was dazed and trying to stand up on his one leg. When the bull threw him up in the air for a second time, the rest of the hunters knew that Jakob had met his end and that he would be blown away by that strong wind to go into the land of stone.

The bull turned around again and was going to stomp the last bit of life out of Jakob and finish him off for good. The hunters witnessed the cloud of dust as the bull trampled him. What they didn’t know was that I decided to save Jakob that day. I dragged the real Jakob off to the fountain and just left a clump of matjies reed in his place for the bull to see. I stopped the bleeding from his upper leg and pushed the two pieces of his broken femur, firmly together. I put an ostrich egg full of water next to him and left him to sleep. Jakob actually survived but no one from that Bushmen clan knew. I hope it taught them a lesson about greediness that day.

The easy part was guiding a boer hunting party towards the fountain, where they would find Jacob, in a fever but still alive.

The same fountain where Sprinkaan just found himself at this point in time. He stood beside the spring, with clear fresh water bubbling out of the heart mountain. Framed by a patch of brilliant green where ferns and moss clung to the wet stone. Waterr that mostly bubbled up from under rocks and in some sandy spots even kicked up some sand as it bubbled to the surface. He filled his bottle – drank most of it and filled it up again.

This narrow beautifully clean stream wound gently across the valley, towards the foot of the mountain about four kilometres on the other side. The waters glinting in the afternoon light as it meandered between clusters of matjiesriet and tall grass. Streaks of thin cloud grew across the sky and the breeze got stronger. He kept a steady pace, north-east now, using the stream as a gentle guide. Many of the ash-green wabome along the way were covered in pink and white flowers.

The boy was obviously struggling with some inner conflict and couldn’t have known that he was heading straight towards Duiwelsberg, Devils Mountain. He needed to make a choice and the temptation of rather following the pinky and not the thumb, was growing. Not that I think the mountain could have any influence on his decision. But I couldn’t help to wonder.

“Follow the water.” Were Jakob’s directions to safer grounds. Which is what he was doing now. The stream bent naturally to the right, at the foot of Duiwelsberg and continued into Baviaanshoek – the safer option. The north-westerly wind cooled and started kicking up dust higher up in the valley.

I can hear him thinking to himself, that if he went around the right of the tip of the mountain, he could find a place that was protected from the wind. I watched him followed the stream to where another joined from the left hand side. Now there was quite a bit more water that formed a pool at the foot of the mountain.

He looked for a convenient open spot along the pool to fill up his water bottle. The wind already felt a lot better on this side of the mountain. Ahead he saw a forest of Cedar trees close to the water and a convenient patch of white sand on both sides of the pool. The water looked shallower there and the game paths indicated that it was a convenient place for crossing the pool.

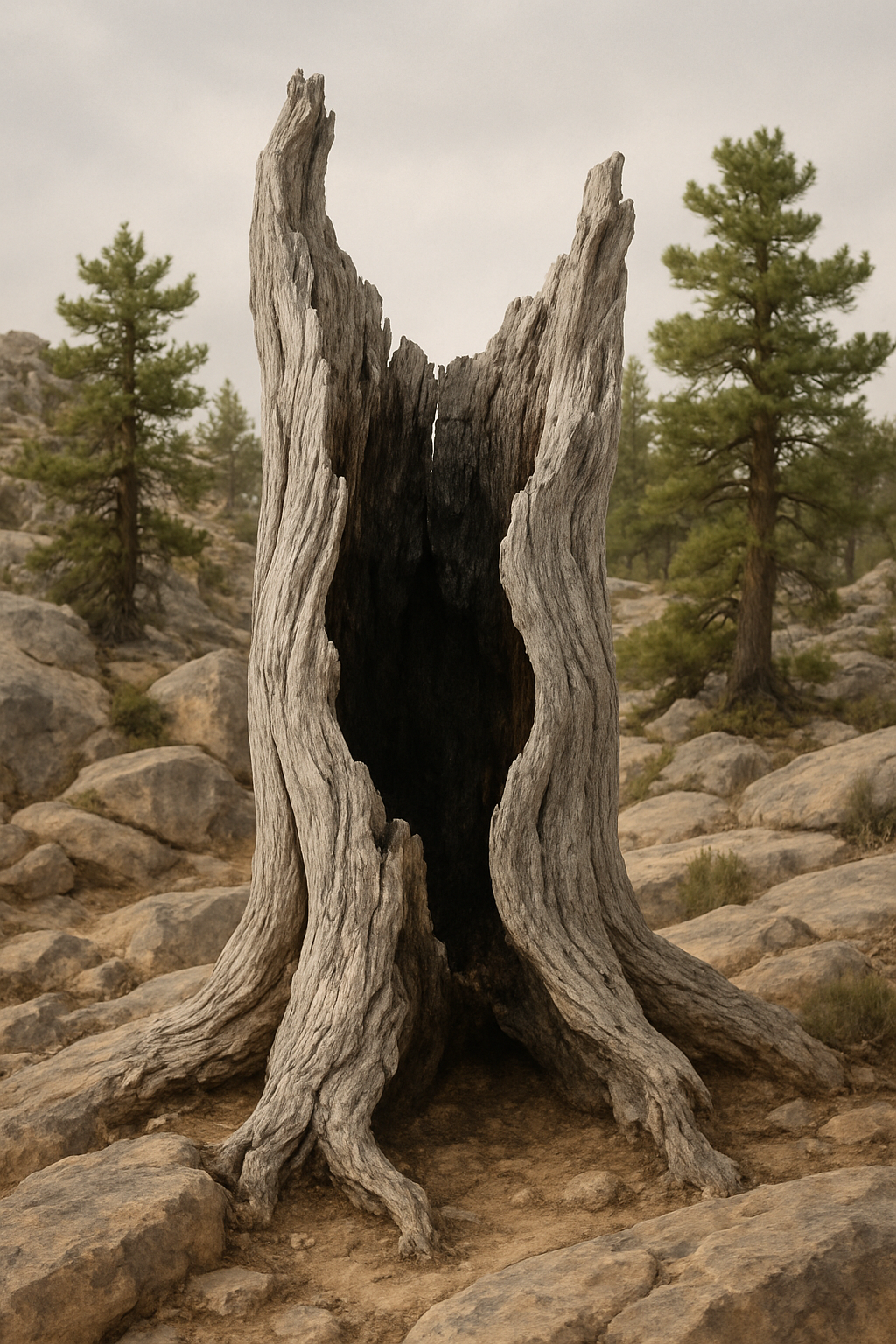

He found a nice spot next to an old burnt-out cedar tree and decided to take a break and enjoy the beautiful surroundings.

Once he scanned beyond the stream a herd of eland, tall and still, came into view. They were about 400 meters away, with their great tan bodies shimmering slightly in the afternoon light, hardly distinguishable from the tall yellow grass that they were grazing on. Some lifted their heads to look around for predators while others, less concerned, chewed slowly, tails flicking flies from their flanks.

The eland slowly grazed closer to us and if not for the wind that blew the boys scent towards them, they would have drank and crossed right in front of us. Instead they headed to the other side of the valley and went for a drink at the fountain. Elandsfontein I heard him think. He was good this one. He remembered the finest detail of what old Jakob told him around the cooking fire in the barn. That must be what Jakob meant. He said the farmers found him at Elandsfontein. That is the place where he was nearly killed by an eland. He never spoke about what exactly happened, just that he fought with this eland that threw him up into the air and that he broke his upper leg in the process. With time the leg healed but he always walked with a limp, almost like Jakob from the bible, the farmers said.

There was something sacred in the stillness and the wide open plains. One could hardly hear the wind but we could clearly see how it blew the grass into waves that were dancing on the plains. It didn’t take long and Sprinkaan thought about Jakob and the eland again.

In Jakob’s stories, the eland was more than just meat — it was a creature of power, almost a spirit in flesh. Especially the great bulls. Jakob used to say that ǃKaggen, the Mantis, once turned himself into an eland. That it was the first animal, the one from which all blessings were drawn. To kill such a creature was no simple act. It meant food, yes — but also firelight, singing, trance, and story. It meant belonging. He wondered what it would be like to belong to a clan of Bushmen and to go out with them hunting for game?

I liked the boy’s thinking.

He decided to rest there a while, beside the pool, under the cedar trees. The sun was still high, but he wanted to watch the eland some more and stay out of the wind for now. He sat their watching the herd for a long time as they headed back towards where they came from. He chewed slowly on his last piece of biltong. The taste of dried beef was simple but honest, and it paired well with the quietness of this place.

After a long time when the eland herd disappeared into Baviaanshoek, he decided to collect some fire wood before it got too dark. He didn’t have anything to cook but a fire always make good company. Because of the wind he cleared a proper space in front of the old burnt-out tree and packed a much higher circle of stones to contain the fire. There were plenty of dry cedar branches around and he knew that he would be able to keep the fire going deep into the night.

He drank in the beauty of the moment and tasted the freedom of being out here in nature. The shadows were growing longer on the plains and the light became softer almost pink on the flanks of the mountains. He noticed that the hill on the other side of the plains, had the same shape as the one on this side, both sloping up towards the west and then suddenly dropping off as kranses on the valley’s side. What could have caused such a big gap between the two parts of the same mountain – surely water alone could not have done this?

I couldn’t help wondering how a 10 year old boy would think about this. Who thinks about geography at that age. He didn’t know the names but I couldn’t help noticing that he was sitting on Duiwelsberg, looking across the gap at Engelkop, Angels Head, exactly five kilometres away as the crow flies. Engelkop was much bigger and a lot higher but who knows how they were formed millions of years ago?

The last of the sunlight painted Engelkop in shades of gold and the moon rose from its bed on the other side of Baviaanshoek. Long streaks of thin clouds gathered overhead almost in defence of the wavering day. On the high ridges the moonlight painted the sandstone silver and whispered across the rough flanks of the Cederberg. The last of the pink and orange drained out of the cirrus clouds and they almost became invisible again.

Sprinkaan leaned against the skeleton of the long-dead cedar. The old trunk still stood, hollowed by time and fire, its grey wood worn smooth like the ribs of a whale. Its base was wide enough for a child to hide inside of it. Sprinkaan smiled. “Klip would say all the old ones remember. Even when they’re dead.” I didn’t hear an answer but much later that evening, something happened -

The flames were burned out already and some shy coals were lying there in a nest of ash. The wind found its way through the line of cedar trees, Sprinkaan stirred from half-sleep with a start. Something had spoken.

Not loudly, not in words he knew. But something. A low murmur—half breath, half voice—curling out of the old cedar’s hollow. It didn’t come all at once, but slowly, like someone waking from a long, slow dream. Sprinkaan sat up, staring wide-eyed into the dark wound, on the side of that old cedar trunk.

“…you… hear…”

The boy sat up and scrambled backwards, his heart thudding like eland hooves on the run.

“There’s something in the tree!” – he said to Klip.

The coals in the nest of ash, glowed brighter as another breeze moved through the trees. This time he could hear it again, like an ancient voice from far away… almost chanting and maybe a voice older than the wind.

“ we burned … too many times … and wish that … we could move where we wanted to.”

Not Xhosa, not Dutch, not any speech he knew—but meaning was there, hovering between the syllables. A sadness. A warning. A memory. A wish.

“…we burned… too many times… the fire forgot to give us back…”

“Who are you?” he asked, not even caring that he might be talking to a ghost. Just in case it was Klip having fun with him.

There was no reply. Just the wind, and the hush of Sprinkaan’s breath in the night.

In the morning, the fire was cold. Sprinkaan stepped up to the tree trunk. Inside, carved faintly in the scorched wood, were lines—some old, some fresh. Bushman marks, almost invisible now. Antelope, long-legged people. And beside them, something new. A child’s handprint as fresh as from yesterday?

Sprinkaan looked for a long time, then nodded. “It heard you,” he said. “And maybe you heard me to?”

He thought about it for a long time and with the extra wood from last night got the fire started again. The air was much cooler this morning, with a lot more cloud. He could see her glow in the west but the moon was completely obscured. He enjoyed the warmth and the company of the fire and wondered if it was going to rain.

The sun was slow to break through the clouds and Sprinkaan was slow to leave the comfort of the fire. I must admit that I also found it hard to get going

Later the bird-like screech of a dassie’s warning, announced that something was on the move.

Funny how that triggered a memory in Sprinkaans mind as he scratches the last of the twigs onto the dying fire. Jakob told him how everyone underestimates dassie. One thing about Jakob – he likes to tell these animal stories.

“She is !Kaggens's wife." Old Jakob said, with eyes widening into a subtle warning.

One day, the leopard called out, sarcastically:

“Dassie, come out of your hiding place and let me see that tail of yours.”

The dassie, cheeky as ever, replied:

“Oh mighty leopard, my tail is weak and tangled—just look at your own glorious tail! Surely you hold more magic than I ever could.”

The leopard growled:

“If you speak so, then dance for me—you love dancing.”

The dassie began to shake herself on the rock—her bottom jiggling like a sack of sand. She thumped it against the stone in a funny, round dance.

The leopard, confused by the odd rhythm, tried to mimic her dance. But his body was too long, his paws too wide. He stumbled, his tail tangled in a crevice. His roar echoed—and the dassie leaped away laughing, her round rump disappearing into a safe crack in the cliff.

From that day, the leopard learned: even the smallest creature has its own magic. And the dassie? She still sits in the rocks, quietly smiling, living on her wits.”

Jakob winked at Sprinkaan.

“So remember, boy—never underestimate the clever sister. Even the claw of the sky can be tricked by her rump on the rock.”

Sprinkaan smiled by himself and I can hear him thinking, that this was a bit of a silly story.